Read the story in Nepali: भारतीय दलालको चंगुलमा नेपाली श्रमिक

--

Chandan Mandal, a 20-year-old from Mithila Municipality-9 Bengadabar in Dhanusha district, had traveled to Srinagar, India, hoping to improve his family's financial situation. He envisioned better earnings, stable employment, and the opportunity to explore Kashmir.

However, his aspirations were quickly dashed.

Forty-two Nepali workers, including Mandal, crossed the Sonbarsha border point between Nepal and India, embarking on a journey fraught with unforeseen challenges and hardships. They were deprived of basic humanitarian aid and had their money, jewelry, and other valuables confiscated by the procurer, who had promised decent work.

Forty-two Nepali workers, including Mandal, crossed the Sonbarsha border point between Nepal and India, embarking on a journey fraught with unforeseen challenges and hardships. They were deprived of basic humanitarian aid and had their money, jewelry, and other valuables confiscated by the procurer, who had promised decent work.

Nepali workers are often lured to India with false promises of easy work, food, accommodation, and higher wages. Indian procurers visit Nepali villages, exploiting unemployed locals to entice other young people with the allure of better job opportunities and income.

Once in India, these workers face immense difficulties finding employment. Even if they manage to secure a job, they struggle to afford basic necessities like food. Many days are spent idle, without work.

Mandal fell victim to this deceitful scheme, lured to India by unscrupulous procurers. He and the other 41 workers were initially paid a small sum of Rs 5,000 to Rs 7,000. However, upon reaching Srinagar, they were held captive and forced to work without additional compensation. The procurer claimed to have purchased Mandal for Rs 7,000.

Mandal managed to escape this ordeal and returned home with Saroj Sada from Sarlahi. Based on the information provided by Mandal, 36 other workers were rescued on May 16, 2024. Twenty-three of the rescued were from Mahottari, 11 from Sarlahi, and two from Dhanusha. They were all between the ages of 15 and 44. Some others had fallen ill and returned to Nepal.

Rina Jha, the coordinator of Peace Rehabilitation Center, Dhanusha, explained that most procurers lure Nepali workers to India with promises of better income and job opportunities. In some cases, even children are taken to India for work. The procurers receive commissions from both employers and workers, creating a system that exploits Nepali workers. These workers are often denied promised jobs, food, and accommodation, and are forced to work excessive hours.

Ram Ekbal Sada from Mahottari was one of the 42 workers who faced this situation. Indian procurers met him in Bardibas and asked him to recruit other young people. With the promise of advance payment of Rs 5,000 to Rs 7,000, Sada convinced unemployed youths to accompany him to India.

Last year, in July or August, Lallan Yadav, an Indian procurer from Madhawapur, visited the Mushahar settlement in Janakpurdham Sub-Metropolis-7 and took 12 workers, including Jhapsa Sada, to Gujarat, India. Jhapsa was initially told that he would be lifting 10-12 kg cotton bags, but once in Gujarat, he was forced to lift 100 kg sacks and carry them to the fourth floor. He was required to work from 8 in the morning till 10 in the night for a meager monthly wage of 10,000 Indian Rupees. Feeling deceived and exploited, Jhapsa wanted to return home.

However, Lallan insisted that he had invested a significant amount of money in bringing them to India and that they would have to complete the work before returning. These 12 Nepali men were subjected to forced labor. Jhapsa stated, "We refused to work and expressed our desire to return home, but he forced us to work late hours every day. All the payment meant for us was taken by Lallan."

According to Jhapsa, young boys who were unable to lift 100 kg were physically abused and forced to complete the task. As they were not provided with adequate food, they seized an opportunity to escape the workplace one night and reached Ahmedabad. There, they worked for a few days in eateries, earned enough money for their travel expenses, and returned home. A few others chose to remain in Ahmedabad. Jhapsa is currently engaged in menial labor in Nepal. He expressed frustration, stating, "If we could find work here in Nepal, why would we go there? Only those with influence and connections secure jobs here."

Exploitation and torture

Forty-two men, including Chandan Mandal, were taken to Badgam, a town near Srinagar, by Indian procurers. They were transported by bus from Sonbarsha, an Indian town bordering Sarlahi. Upon arrival, they were confined to a warehouse-like room and subjected to severe exploitation, according to Chandan.

They endured physical abuse, including beatings with belts and canes, forced humiliation, and threats of violence. The workers were forced to perform degrading acts and were constantly intimidated. Chandan recalled the contractor's threats, "If you speak up, we will kill you and throw you away."

Chandan and his fellow workers were promised employment in drainage ditch construction, but were instead forced to work on building construction sites, erecting concrete slabs. For a month and a half, they endured extreme torture and exploitation and they decided to flee one day. “We faced extreme torture and exploitation, hence Saroj and I took a risk one day and escaped,” Chandan said. They ran away while slab work was going on by jumping off the compound wall and reached a military camp in about 10 minutes. On reaching the military camp they narrated their story to the guard there but the soldier suspected them of being terrorists. “We thought, as Gorkhas and Nepalis, we would be believed. Instead, we were mistaken for terrorists,” said Chandan. “We told him the entire story, and he advised us to go to the police.”

While on their way, they met a traffic policeman and told him about their plight. On hearing their story, the traffic police helped them hitch a ride on a truck to Jammu. They were tired and hungry. “The truck driver gave us two biscuits each. We ate the biscuits and continued the journey.” “I don’t remember the names of the places but the truck driver took us to another traffic police at around nine in the evening and dropped us there,” said Chandan. When Chandan narrated his story to the new traffic police, the police was kind enough to give him 550 Indian Rupees and 250 Indian Rupees to Saroj. The police also helped them to get on to a pick-up truck which took them to the railway station in Udhampur and left them there. They purchased two train tickets for Rs 70 each and left for Jammu.

From Jammu, they took a train to New Delhi by which time they had used up all the money they had. “Though we did not have any money, we boarded a train in Delhi but in Sonpur the train authorities asked us for tickets. Since we did not have any tickets we decided to get off from that train and boarded another train to Jayanagar,” Chandan said. After reaching Jayanagar, they walked all the way to Janakpur. According to Chandan, they heaved a huge sigh of relief when they crossed over the border to Nepal. They had felt like they had just won a huge battle.

Back home, Chandan now works as a truck driver and is preparing to go abroad for employment. “If we were able to find decent jobs in Nepal, nobody would want to leave their homes. Here in Nepal, we get work for one day and have to manage our basic needs for another 10 days with what we earn on that day. How is that possible? This is the main reason why unemployed Nepali men fall into the job trap set by unscrupulous strangers and reach India,” he said.

Rescue efforts from the Indian side

Saroj Ray was instrumental in rescuing the stranded Nepali workers in Srinagar. After Chandan returned home and informed the families of the workers about their captivity and forced labor, the families sought help from various authorities, organizations, and individuals. Chandan recounted, "After returning, I approached Raghubir Mahaseth (the MP) and the CDO office, but they didn't offer any assistance. Then, I contacted Saroj Sir, who was the one who helped us."

Rajib, brother of Ranjit Chaudhary, who at that time was living in Saudi Arabia, had already contacted Saroj and informed him about the plight of his brother, and requested him for help. While Saroj didn't have specific details at the time, the meeting with Chandan shed light on the severity of the situation.

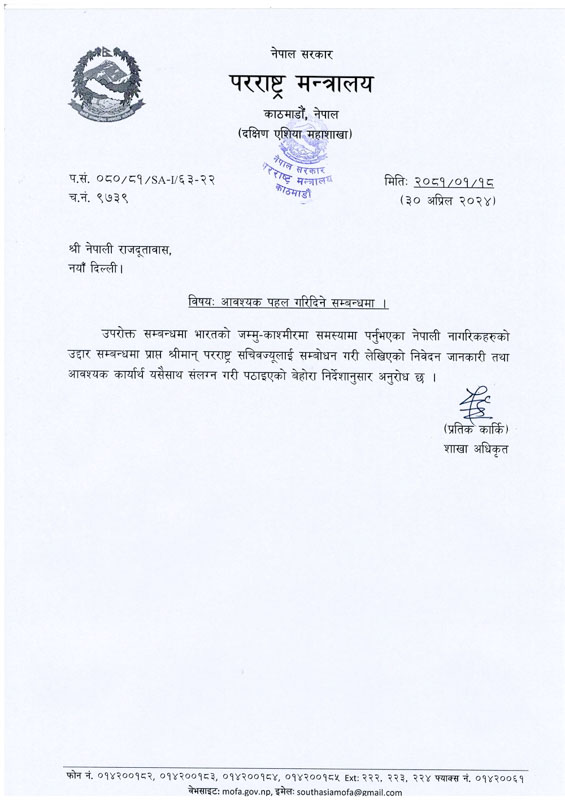

Saroj promptly took action. First, he compiled a list of the Nepalis stranded in Srinagar. Then, on April 29, 2024, he brought the issue to the attention of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, highlighting the plight of the Nepali workers trapped in Kashmir. The Ministry subsequently communicated the matter to the Embassy of Nepal in New Delhi.

Saroj, Chandan, and other relatives of the workers traveled to India and, with the assistance of Keen India, an Indian NGO, and the Indian Police, successfully rescued the workers. Chandan, in disguise, led the activists to the location in Srinagar where the workers were held captive. On May 10, 2024, Chandan and the undercover Indian police identified the house where the Nepali workers were confined. The police then raided the premises and rescued them. According to Saroj, the workers were crammed into two basement rooms, locked from both the inside and outside.

Initially, the workers did not believe when the Nepali team said they were there to rescue the workers. Only when they saw their relatives did the workers believe that the team had come to rescue them. “The working and living condition of the workers there was pathetic,” Saroj recalled. "Everyone was crying and complaining. They were locked inside, severely beaten, and not even allowed to go outside to relieve themselves," Saroj recounted. "To prevent the workers from escaping, the contractor would lock the door from outside and sleep in the same room," he added.

These Nepali workers had toiled for 85 days without receiving a single penny, except for an advance payment of Rs 5,000 to Rs 7,000 each before leaving their homes. They finally returned home on May 16, 2024.

During the raid, six Indians involved in the forced labor of the Nepali workers were present. Four managed to escape, while two were arrested by the Indian police. Saroj explained, "As we couldn't identify all the contractors, four of them escaped, but two, Muktakim Alam and Sajad, who were the main culprits, were arrested."

The Indian police have initiated legal proceedings against the arrested individuals based on the complaints filed by the Nepali workers. Nabin Joshi, the president of Keen India, an Indian NGO that coordinated the rescue efforts, revealed that they have successfully rescued over 700 Nepali workers. He highlighted the tactics employed by agents (procurers) from Bihar, who lure Nepali individuals from the Tarai Madhesh region to India.

According to Saroj, the procurers had taken stock of the ground reality of Nepal prior to taking 42 workers to India five months before. “Most of the times they target people from poor and deprived families, especially those who belong to the Mushahar community. This is their modus operandi, however we do not have any documents or any kind of proof against them,” said Saroj.

According to him, the contractors who come to Saptari to lure Nepalis are from Araria, a town across the border.

The government maintains records of individuals leaving the country using passports but lacks data on the number of Nepalis who migrate to India for work. These workers often lack job security and healthcare benefits. Saroj questioned, "All Nepalis, regardless of whether they hold passports or not, are citizens. Why is there such discrimination?" To prevent Nepali workers from enduring the torture and hardships experienced in Kashmir, Saroj suggests implementing a policy that mandates obtaining a labor permit from the Nepali government before migrating to India for work.

Local administrations often lack awareness about workers who migrate to India. Despite the rescue and return of the Nepali workers from Srinagar, the local administration in Mahottari, for example, remains uninformed. Shivaram Gelal, the Chief District Officer (CDO) of Mahottari, admitted to being unaware of the situation. When asked if the families of the victims had sought assistance from the local administration, he replied, "The office is obligated to help those who approach us with complaints. We are unaware of any such interactions."

False business promise

Nepalis are often lured to India with promises of business opportunities. Lilaram Chapagain, a 47-year-old from Kawasoti Municipality-2, Nawalparasi district, is one such example. A returning migrant, he was struggling to make a living from his grocery shop. A friend convinced him that he could earn substantial sums of money in India. On May 22, 2024, Chapagain was taken to the Modern Fashion Networking Company in Muzaffarpur, India. Initially, he was promised a job in clothing packaging followed by business training. He was required to pay a training fee of Rs 10,000. During his stay in the company's hostel, he realized he had been deceived into a multi-level marketing scheme.

He was then informed that after completing the training, he would need to pay a membership fee of Rs 150,000 to earn a commission of Rs 120,000 by recruiting three more members. The more members he recruited, the higher his commission would be. Recognizing the illegal nature of multi-level marketing in Nepal, Lilaram decided to cut his losses and return home. "I was losing Rs 10,000, but staying would have risked losing up to Rs 200,000. When the seven-day training ended, I told them I would bring the money from home and escaped," he recalled.

Lilaram mentioned that several other Nepali youths were undergoing training alongside him in India. "In one seminar, there were around 600 Nepalis," he stated, highlighting the significant number of Nepalis who fall victim to false promises and deception in India. Lilaram revealed that some of these deceived Nepalis, after returning from their training, turn into recruiters, luring their relatives and acquaintances into the same trap. He cautioned, "No one should fall for such schemes. They are mere traps designed to deceive innocent people."

Lilaram explained that the training sessions were held in a company hall near the Khabada Mankamana Baba temple in Muzaffarpur. The trainees were accommodated in a nearby hostel. Company personnel provided transportation to and from the training center. The trainees were strictly prohibited from interacting with outsiders, retaining training materials, or using mobile phones within the training halls. This restriction prevented Lilaram from capturing any evidence of the activities inside the hall.

(This investigative report was prepared through the NIMJN fellowship supported by the Australian Aid. All rights reserved with the author and publisher.)

Read our Republishing Policy here.